This time of year I can’t help but feel nostalgic for one of Pensacola’s lost legacies, St. Anne’s Roundup.

St. Anne’s is a Catholic Church on Pensacola’s west side, and for forty years it hosted the western themed Roundup, one of the most beloved and popular festivals Pensacola ever produced. It was such a popular event that in 1992 over 200,000 people attended and it was simply amazing. It’s easy to find Pensacolians 25 years of age and older who have quite fond memories of the Roundup.

It all began in May of 1964 when Father John A. Lacari held a parish fund-raising dinner with a western theme. It was so successful that he built it into the annual St. Anne’s Roundup, a full three days of Western flare on the first weekend of every October, drawing in huge crowds from all over the area.

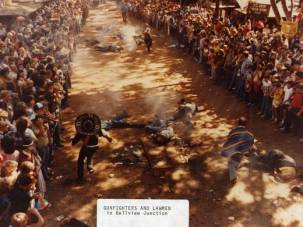

Father Lacari had a small mock western styled ghost town constructed in the pecan grove behind the church and named it Bellview Junction in honor of the census designated place just outside the Pensacola city limits where the church is located. The buildings housed numerous food and refreshment stands, games, and a photo booth where people could dress in period clothing and have their picture taken. The main activities and entertainment took place out front of Miss Kitty’s Saloon at the end of the main street called Sweatfager Trail. Here was a mockup saloon that acted as a prepping area for bands and other acts that would be featured on the main stage built onto the front porch.

The main stage hosted local and regional bands, comedians, various dance groups, and was used to announce the winners of the various raffles and announce other business. Each year the Roundup hosted a celebrity guest such as John Schneider at the height of his Dukes of Hazzard fame, Heather Locklear in 1983, John Ritter in 1993 and many others who would speak, answer questions, pose for pictures and sign autographs.

One of the corner stone acts were the cancan dancers who were an inextricable part of the Roundup’s entertainment, performing multiple times each day. Immediately following the cancan dancers the street would be cleared with attendees instructed to move to either side and a reenactment gunfight would be performed by specially trained actors. This usually involved a short skit of lawmen versus outlaws resulting in one side emerging victorious over the other in a dramatic shootout complete with realistic looking and sounding guns firing blanks, filling the air with smoke and the scent of gunpowder.

The most enjoyable part of the Roundup for me was the “jail.” This was the station I liked to work in the best. About midway down the Sweatfager Trail was a little jailhouse with a pen made with chicken wire inside of which were several long benches to house the “prisoners”. A sheriff was in charge of organizing the several volunteer deputies. The deputies, usually teenage boys were issued little tin badges and their job was to arrest random people from the crowd on whatever false or factual charges they could imagine. Wearing blue on the street, carrying a corndog with your left hand, or anything could serve as a charge. For a few bucks someone could fill out a warrant and have a specific target, a relative or a friend arrested. In most cases the people played along and went off to the jail in good spirits where for a dollar donation they could post bail, or hangout behind the wire and be a part of the show until being released after several minutes. I worked as a deputy a few different times, and one year my father worked as the sheriff. It served as a fun and lucrative fundraiser for the church.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about the Roundup was how the whole community seemed to come together to support it. Local food and refreshment providers donated resources and time, businesses made donations of various products for raffles, and prizes for the Roundup Princesses (did I mention there was a yearly princess?). High school marching bands came out to perform. The McGuire’s Pipe Band performed each year. Local businesses would pay top dollar for advertizing either on strategically placed signs or in the Bellview Gazette, the Roundup’s annual news journal. One year Ted Ciano donated a new car to be raffled off. On top of that, it seemed like everyone in the Pensacola area attended. People came in from out of state to attend. It really was a sight that is impossible to describe adequately. This all resulted in St. Anne’s being the most financially successful parish in the Diocese.

Sadly, Father Lacari suffered a heart attack and retired in 1993. He died shortly afterward. His successor was never able to do justice for the Roundup or the church and it began to lose its brilliance until 2004 when Hurricane Ivan swept through, destroying Bellview Junction.

Since that time the church has been unwilling to even attempt to revive or rebuild the Roundup even in a revised form as they struggle financially despite a significant desire from the greater community for it to do so. It is now just another one of Pensacola’s lost legacies.

When I first started writing this article it was intended to be one of the first hints to begin promoting what would be a New Roundup at St. Anne’s beginning in 2019. It was an ambitious dream. I thought we were very close to achieving it, but for reasons outside the scope of this article the project was aborted. I decided to finish the article as a memory rather than as the pre-promotional it was intended to be.

Fidelium animae, per misericordiam Dei, requiescant in pace. Amen.